Last week the UK government effectively nationalised the blast furnaces at Scunthorpe on the north-east coast of England. These furnaces are the last sites in the UK that can manufacture iron from ore as a precursor to the production of virgin steel. The emergency legislation will help to keep open this important source of local employment and industrial activity.

Nevertheless, I argue that it was an expensive and unnecessary move. Instead of making new virgin steel, the UK should concentrate on recycling the large amounts of old scrap steel that are exported from this country for reprocessing around the world. The owners of Scunthorpe already have plans to switch to using steel using electricity and scrap. Of critical importance to any plan, the price of electricity used for electric arc furnaces needs to be roughly the same as in competitor countries, necessitating a substantial subsidy. Without it, UK steel-making cannot hope to be financially self-reliant. Other countries do this and without financial support, the UK cannot hope to be competitive.

Basic numbers

The most recent data from industry body UK Steel gives the following figures for the UK’s consumption and production of steel. These figures relate to 2023. In 1970, the peak year for the country’s steel production, the number was five times higher.

UK Production of steel - 5.6 million tonnes, of which 4.5 million tonnes came from blast furnaces

UK Demand for steel - 7.6 million tonnes

So about 2m tonnes of steel had to be imported in 2023. This number probably rose in 2024 after the closure of the blast furnaces at Port Talbot but the figures are not publicly available yet.

But at the same time as importing 2m tonnes of finished metal, the UK collected about 10.5 million tonnes of scrap steel, almost three million tonnes more than total steel demand in the country. Some scrap was used in the existing electric arc furnaces here but most was exported; about 8.5m tonnes of scrap was sent abroad for reprocessing elsewhere back into new steel. (Some of this new steel will have eventually come back to the UK). This makes the UK the world’s second largest exporter of scrap steel for recycling. Expressed in per capita terms, the country is the top source of used steel.

Put another way, the country’s exports of scrap, which can be easily recycled in electric arc furnaces, alone exceeded its total demand for the metal. There is no need for blast furnaces, such as the ones in Scunthorpe, for the UK to build self-sufficiency in steel production. This has been a consistent worry expressed over recent weeks with many expressing a view that the UK needed to retain the capability to make steel from iron ore in blast furnaces. But simply keeping used steel available for recycling in the UK would provide enough of the metal for the country’s needs.

It may be worth noting that many other countries restrict or block the export of steel scrap in order to ensure adequate supplies for recycling in local electric arc furnaces.

What is stopping the UK switching from blast furnaces to make the metal, rather than using scrap steel?

· Large electric arc furnaces (EAFs) for recycling steel are expensive to construct. The EAFs to be constructed by Tata Steel at Port Talbot in South Wales are projected to cost around £1.25bn for a projected capacity of 3m tonnes a year (or potentially around 40% of the UK’s total steel needs). The government has committed £500m to assist the transition there from blast furnaces to EAFs.

British Steel (owned by Jingye of China) has stated that the cost of creating two new EAFs on the north east coast will also be about £1.25 billion. The projected total capacity doesn’t appear to have been published but based on the Tata numbers we can perhaps assume a similar figure of about 3m tonnes a year.

· UK electricity costs are higher than nearby countries. Even after the government intervention to reduce the costs of electricity transmission to steelworks, one recent study suggests that the British steel industry pays £66 a megawatt hour (MWh) compared to £50 in Germany and £43 in France.[1] Because electric arc furnaces use about 0.5 MWh per tonne of steel output, these higher costs can mean a handicap of £11.50 a tonne of steel from an EAF. At current finished steel prices of around £500 a tonne ($660), this imposes a burden of over 2%. In a low margin industry such as steelmaking, this difference is significant.

· Falling UK demand for steel has imposed an additional weight on investment enthusiasm. Investing £1.25bn in a shrinking market looks a dangerous decision to take. On the other hand, some demand increases are likely in future; wind turbine columns alone might add 1m tonnes a year to UK needs.

· EAFs need far fewer employees per tonne of output, making it politically difficult to allow the closure of a major source of local employment in Scunthorpe. And any new EAFs in that part of the UK will take several years before they begin to hire permanent staff.

The advantages of using EAFs rather than keeping the Scunthorpe blast furnaces open

· EAFs use local scrap metal, reducing the amount exported.

· The UK scrap also contains other metals, such as copper, increasing its value and reducing the need to import materials.

· EAFs produce much less local air pollution than the older steel-making method.

· The carbon footprint of EAFs is about one sixth of steel originating in blast furnaces. The figures will depend on the fossil fuel intensity of the electricity used but most sources estimate a footprint of about 0.35 tonnes of CO2 per tonne of steel, compared to about 2 tonnes from the blast furnace route. Replacing the 2023 4.5 million tonnes of steel with EAF output would save about 7.4 million tonnes of CO2 or just under 2% of UK emissions.

· Potentially the economics of using scrap could be better. The open market scrap price is around $350 per tonne, equivalent to £263 today, or just over half the value of a tonne of steel in the UK. The price of raw materials is likely to be more stable, avoiding the need to have to buy much coking coal and iron ore on international markets.[2]

· EAFs can help stabilise the electricity market, using power mostly at times when the wind is blowing and not at times of scarcity. Unlike blast furnaces, EAFs can decide when to operate. While not a trivial exercise, steel-making can adjust its demand to match national supplies of electricity.

In summary, both industrial strategy and carbon reduction aims should push us towards EAFs rather than keeping open the Scunthorpe blast furnaces. It makes very little sense to spend large sums keeping the furnaces open rather than sponsoring the building of new EAFs when the UK has such abundant supplies of metal for recycling and the carbon footprint benefits may be equal to at least one per cent of the UK emissions. This is not to dismiss the profound social consequences of the reduced employment prospects for steelworkers in the Scunthorpe area.

[1] <a href="https://www.uksteel.org/electricity-prices" rel="nofollow">https://www.uksteel.org/electricity-prices</a>

[2] EAFs use some iron ore and some coal but in much smaller quantities than blast furnaces.

English speakers know that their language is odd. So do people saddled with learning it non-natively. The oddity that we all perceive most readily is its spelling, which is indeed a nightmare. In countries where English isn’t spoken, there is no such thing as a ‘spelling bee’ competition. For a normal language, spelling at least pretends a basic correspondence to the way people pronounce the words. But English is not normal.

Spelling is a matter of writing, of course, whereas language is fundamentally about speaking. Speaking came long before writing, we speak much more, and all but a couple of hundred of the world’s thousands of languages are rarely or never written. Yet even in its spoken form, English is weird. It’s weird in ways that are easy to miss, especially since Anglophones in the United States and Britain are not exactly rabid to learn other languages. But our monolingual tendency leaves us like the proverbial fish not knowing that it is wet. Our language feels ‘normal’ only until you get a sense of what normal really is.

There is no other language, for example, that is close enough to English that we can get about half of what people are saying without training and the rest with only modest effort. German and Dutch are like that, as are Spanish and Portuguese, or Thai and Lao. The closest an Anglophone can get is with the obscure Northern European language called Frisian: if you know that tsiis is cheese and Frysk is Frisian, then it isn’t hard to figure out what this means: Brea, bûter, en griene tsiis is goed Ingelsk en goed Frysk. But that sentence is a cooked one, and overall, we tend to find that Frisian seems more like German, which it is.

We think it’s a nuisance that so many European languages assign gender to nouns for no reason, with French having female moons and male boats and such. But actually, it’s us who are odd: almost all European languages belong to one family – Indo-European – and of all of them, English is the only one that doesn’t assign genders that way.

More weirdness? OK. There is exactly one language on Earth whose present tense requires a special ending only in the third‑person singular. I’m writing in it. I talk, you talk, he/she talk-s – why just that? The present‑tense verbs of a normal language have either no endings or a bunch of different ones (Spanish: hablo, hablas, habla). And try naming another language where you have to slip do into sentences to negate or question something. Do you find that difficult? Unless you happen to be from Wales, Ireland or the north of France, probably.

Why is our language so eccentric? Just what is this thing we’re speaking, and what happened to make it this way?

English started out as, essentially, a kind of German. Old English is so unlike the modern version that it feels like a stretch to think of them as the same language at all. Hwæt, we gardena in geardagum þeodcyninga þrym gefrunon – does that really mean ‘So, we Spear-Danes have heard of the tribe-kings’ glory in days of yore’? Icelanders can still read similar stories written in the Old Norse ancestor of their language 1,000 years ago, and yet, to the untrained eye, Beowulf might as well be in Turkish.

The first thing that got us from there to here was the fact that, when the Angles, Saxons and Jutes (and also Frisians) brought their language to England, the island was already inhabited by people who spoke very different tongues. Their languages were Celtic ones, today represented by Welsh, Irish and Breton across the Channel in France. The Celts were subjugated but survived, and since there were only about 250,000 Germanic invaders – roughly the population of a modest burg such as Jersey City – very quickly most of the people speaking Old English were Celts.

Crucially, their languages were quite unlike English. For one thing, the verb came first (came first the verb). But also, they had an odd construction with the verb do: they used it to form a question, to make a sentence negative, and even just as a kind of seasoning before any verb. Do you walk? I do not walk. I do walk. That looks familiar now because the Celts started doing it in their rendition of English. But before that, such sentences would have seemed bizarre to an English speaker – as they would today in just about any language other than our own and the surviving Celtic ones. Notice how even to dwell upon this queer usage of do is to realise something odd in oneself, like being made aware that there is always a tongue in your mouth.

At this date there is no documented language on earth beyond Celtic and English that uses do in just this way. Thus English’s weirdness began with its transformation in the mouths of people more at home with vastly different tongues. We’re still talking like them, and in ways we’d never think of. When saying ‘eeny, meeny, miny, moe’, have you ever felt like you were kind of counting? Well, you are – in Celtic numbers, chewed up over time but recognisably descended from the ones rural Britishers used when counting animals and playing games. ‘Hickory, dickory, dock’ – what in the world do those words mean? Well, here’s a clue: hovera, dovera, dick were eight, nine and ten in that same Celtic counting list.

pretty soon their bad Old English was real English, and here we are today: the Scandies made English easier

The second thing that happened was that yet more Germanic-speakers came across the sea meaning business. This wave began in the ninth century, and this time the invaders were speaking another Germanic offshoot, Old Norse. But they didn’t impose their language. Instead, they married local women and switched to English. However, they were adults and, as a rule, adults don’t pick up new languages easily, especially not in oral societies. There was no such thing as school, and no media. Learning a new language meant listening hard and trying your best. We can only imagine what kind of German most of us would speak if this was how we had to learn it, never seeing it written down, and with a great deal more on our plates (butchering animals, people and so on) than just working on our accents.

As long as the invaders got their meaning across, that was fine. But you can do that with a highly approximate rendition of a language – the legibility of the Frisian sentence you just read proves as much. So the Scandinavians did pretty much what we would expect: they spoke bad Old English. Their kids heard as much of that as they did real Old English. Life went on, and pretty soon their bad Old English was real English, and here we are today: the Scandies made English easier.

I should make a qualification here. In linguistics circles it’s risky to call one language ‘easier’ than another one, for there is no single metric by which we can determine objective rankings. But even if there is no bright line between day and night, we’d never pretend there’s no difference between life at 10am and life at 10pm. Likewise, some languages plainly jangle with more bells and whistles than others. If someone were told he had a year to get as good at either Russian or Hebrew as possible, and would lose a fingernail for every mistake he made during a three-minute test of his competence, only the masochist would choose Russian – unless he already happened to speak a language related to it. In that sense, English is ‘easier’ than other Germanic languages, and it’s because of those Vikings.

Old English had the crazy genders we would expect of a good European language – but the Scandies didn’t bother with those, and so now we have none. Chalk up one of English’s weirdnesses. What’s more, the Vikings mastered only that one shred of a once-lovely conjugation system: hence the lonely third‑person singular –s, hanging on like a dead bug on a windshield. Here and in other ways, they smoothed out the hard stuff.

They also followed the lead of the Celts, rendering the language in whatever way seemed most natural to them. It is amply documented that they left English with thousands of new words, including ones that seem very intimately ‘us’: sing the old song ‘Get Happy’ and the words in that title are from Norse. Sometimes they seemed to want to stake the language with ‘We’re here, too’ signs, matching our native words with the equivalent ones from Norse, leaving doublets such as dike (them) and ditch (us), scatter (them) and shatter (us), and ship (us) vs skipper (Norse for ship was skip, and so skipper is ‘shipper’).

But the words were just the beginning. They also left their mark on English grammar. Blissfully, it is becoming rare to be taught that it is wrong to say Which town do you come from?, ending with the preposition instead of laboriously squeezing it before the wh-word to make From which town do you come? In English, sentences with ‘dangling prepositions’ are perfectly natural and clear and harm no one. Yet there is a wet-fish issue with them, too: normal languages don’t dangle prepositions in this way. Spanish speakers: note that El hombre quien yo llegué con (‘The man whom I came with’) feels about as natural as wearing your pants inside out. Every now and then a language turns out to allow this: one indigenous one in Mexico, another one in Liberia. But that’s it. Overall, it’s an oddity. Yet, wouldn’t you know, it’s one that Old Norse also happened to permit (and which Danish retains).

as if all this wasn’t enough, English got hit by a firehose spray of words from yet more languages

We can display all these bizarre Norse influences in a single sentence. Say That’s the man you walk in with, and it’s odd because 1) the has no specifically masculine form to match man, 2) there’s no ending on walk, and 3) you don’t say ‘in with whom you walk’. All that strangeness is because of what Scandinavian Vikings did to good old English back in the day.

Finally, as if all this wasn’t enough, English got hit by a firehose spray of words from yet more languages. After the Norse came the French. The Normans – descended from the same Vikings, as it happens – conquered England, ruled for several centuries and, before long, English had picked up 10,000 new words. Then, starting in the 16th century, educated Anglophones developed a sense of English as a vehicle of sophisticated writing, and so it became fashionable to cherry-pick words from Latin to lend the language a more elevated tone.

It was thanks to this influx from French and Latin (it’s often hard to tell which was the original source of a given word) that English acquired the likes of crucified, fundamental, definition and conclusion. These words feel sufficiently English to us today, but when they were new, many persons of letters in the 1500s (and beyond) considered them irritatingly pretentious and intrusive, as indeed they would have found the phrase ‘irritatingly pretentious and intrusive’. (Think of how French pedants today turn up their noses at the flood of English words into their language.) There were even writerly sorts who proposed native English replacements for those lofty Latinates, and it’s hard not to yearn for some of these: in place of crucified, fundamental, definition and conclusion, how about crossed, groundwrought, saywhat, and endsay?

But language tends not to do what we want it to. The die was cast: English had thousands of new words competing with native English words for the same things. One result was triplets allowing us to express ideas with varying degrees of formality. Help is English, aid is French, assist is Latin. Or, kingly is English, royal is French, regal is Latin – note how one imagines posture improving with each level: kingly sounds almost mocking, regal is straight-backed like a throne, royal is somewhere in the middle, a worthy but fallible monarch.

Then there are doublets, less dramatic than triplets but fun nevertheless, such as the English/French pairs begin and commence, or want and desire. Especially noteworthy here are the culinary transformations: we kill a cow or a pig (English) to yield beef or pork (French). Why? Well, generally in Norman England, English-speaking labourers did the slaughtering for moneyed French speakers at table. The different ways of referring to meat depended on one’s place in the scheme of things, and those class distinctions have carried down to us in discreet form today.

Caveat lector, though: traditional accounts of English tend to oversell what these imported levels of formality in our vocabulary really mean. It is sometimes said that they alone make the vocabulary of English uniquely rich, which is what Robert McCrum, William Cran and Robert MacNeil claim in the classic The Story of English (1986): that the first load of Latin words actually lent Old English speakers the ability to express abstract thought. But no one has ever quantified richness or abstractness in that sense (who are the people of any level of development who evidence no abstract thought, or even no ability to express it?), and there is no documented language that has only one word for each concept. Languages, like human cognition, are too nuanced, even messy, to be so elementary. Even unwritten languages have formal registers. What’s more, one way to connote formality is with substitute expressions: English has life as an ordinary word and existence as the fancy one, but in the Native American language Zuni, the fancy way to say life is ‘a breathing into’.

Even in English, native roots do more than we always recognise. We will only ever know so much about the richness of even Old English’s vocabulary because the amount of writing that has survived is very limited. It’s easy to say that comprehend in French gave us a new formal way to say understand – but then, in Old English itself, there were words that, when rendered in Modern English, would look something like ‘forstand’, ‘underget’, and ‘undergrasp’. They all appear to mean ‘understand’, but surely they had different connotations, and it is likely that those distinctions involved different degrees of formality.

Nevertheless, the Latinate invasion did leave genuine peculiarities in our language. For instance, it was here that the idea that ‘big words’ are more sophisticated got started. In most languages of the world, there is less of a sense that longer words are ‘higher’ or more specific. In Swahili, Tumtazame mbwa atakavyofanya simply means ‘Let’s see what the dog will do.’ If formal concepts required even longer words, then speaking Swahili would require superhuman feats of breath control. The English notion that big words are fancier is due to the fact that French and especially Latin words tend to be longer than Old English ones – end versus conclusion, walk versus ambulate.

The multiple influxes of foreign vocabulary also partly explain the striking fact that English words can trace to so many different sources – often several within the same sentence. The very idea of etymology being a polyglot smorgasbord, each word a fascinating story of migration and exchange, seems everyday to us. But the roots of a great many languages are much duller. The typical word comes from, well, an earlier version of that same word and there it is. The study of etymology holds little interest for, say, Arabic speakers.

this muttly vocabulary is a big part of why there’s no language so close to English that learning it is easy

To be fair, mongrel vocabularies are hardly uncommon worldwide, but English’s hybridity is high on the scale compared with most European languages. The previous sentence, for example, is a riot of words from Old English, Old Norse, French and Latin. Greek is another element: in an alternate universe, we would call photographs ‘lightwriting’. According to a fashion that reached its zenith in the 19th century, scientific things had to be given Greek names. Hence our undecipherable words for chemicals: why can’t we call monosodium glutamate ‘one-salt gluten acid’? It’s too late to ask. But this muttly vocabulary is one of the things that puts such a distance between English and its nearest linguistic neighbours.

And finally, because of this firehose spray, we English speakers also have to contend with two different ways of accenting words. Clip on a suffix to the word wonder, and you get wonderful. But – clip on an ending to the word modern and the ending pulls the accent ahead with it: MO-dern, but mo-DERN-ity, not MO-dern-ity. That doesn’t happen with WON-der and WON-der-ful, or CHEER-y and CHEER-i-ly. But it does happen with PER-sonal, person-AL-ity.

What’s the difference? It’s that -ful and -ly are Germanic endings, while -ity came in with French. French and Latin endings pull the accent closer – TEM-pest, tem-PEST-uous – while Germanic ones leave the accent alone. One never notices such a thing, but it’s one way this ‘simple’ language is actually not so.

Thus the story of English, from when it hit British shores 1,600 years ago to today, is that of a language becoming delightfully odd. Much more has happened to it in that time than to any of its relatives, or to most languages on Earth. Here is Old Norse from the 900s CE, the first lines of a tale in the Poetic Edda called The Lay of Thrym. The lines mean ‘Angry was Ving-Thor/he woke up,’ as in: he was mad when he woke up. In Old Norse it was:

Vreiðr vas Ving-Þórr / es vaknaði.

The same two lines in Old Norse as spoken in modern Icelandic today are:

Reiður var þá Vingþórr / er hann vaknaði.

You don’t need to know Icelandic to see that the language hasn’t changed much. ‘Angry’ was once vreiðr; today’s reiður is the same word with the initial v worn off and a slightly different way of spelling the end. In Old Norse you said vas for was; today you say var – small potatoes.

In Old English, however, ‘Ving-Thor was mad when he woke up’ would have been Wraþmod wæs Ving-Þórr/he áwæcnede. We can just about wrap our heads around this as ‘English’, but we’re clearly a lot further from Beowulf than today’s Reykjavikers are from Ving-Thor.

Thus English is indeed an odd language, and its spelling is only the beginning of it. In the widely read Globish (2010), McCrum celebrates English as uniquely ‘vigorous’, ‘too sturdy to be obliterated’ by the Norman Conquest. He also treats English as laudably ‘flexible’ and ‘adaptable’, impressed by its mongrel vocabulary. McCrum is merely following in a long tradition of sunny, muscular boasts, which resemble the Russians’ idea that their language is ‘great and mighty’, as the 19th-century novelist Ivan Turgenev called it, or the French idea that their language is uniquely ‘clear’ (Ce qui n’est pas clair n’est pas français).

However, we might be reluctant to identify just which languages are not ‘mighty’, especially since obscure languages spoken by small numbers of people are typically majestically complex. The common idea that English dominates the world because it is ‘flexible’ implies that there have been languages that failed to catch on beyond their tribe because they were mysteriously rigid. I am not aware of any such languages.

What English does have on other tongues is that it is deeply peculiar in the structural sense. And it became peculiar because of the slings and arrows – as well as caprices – of outrageous history.

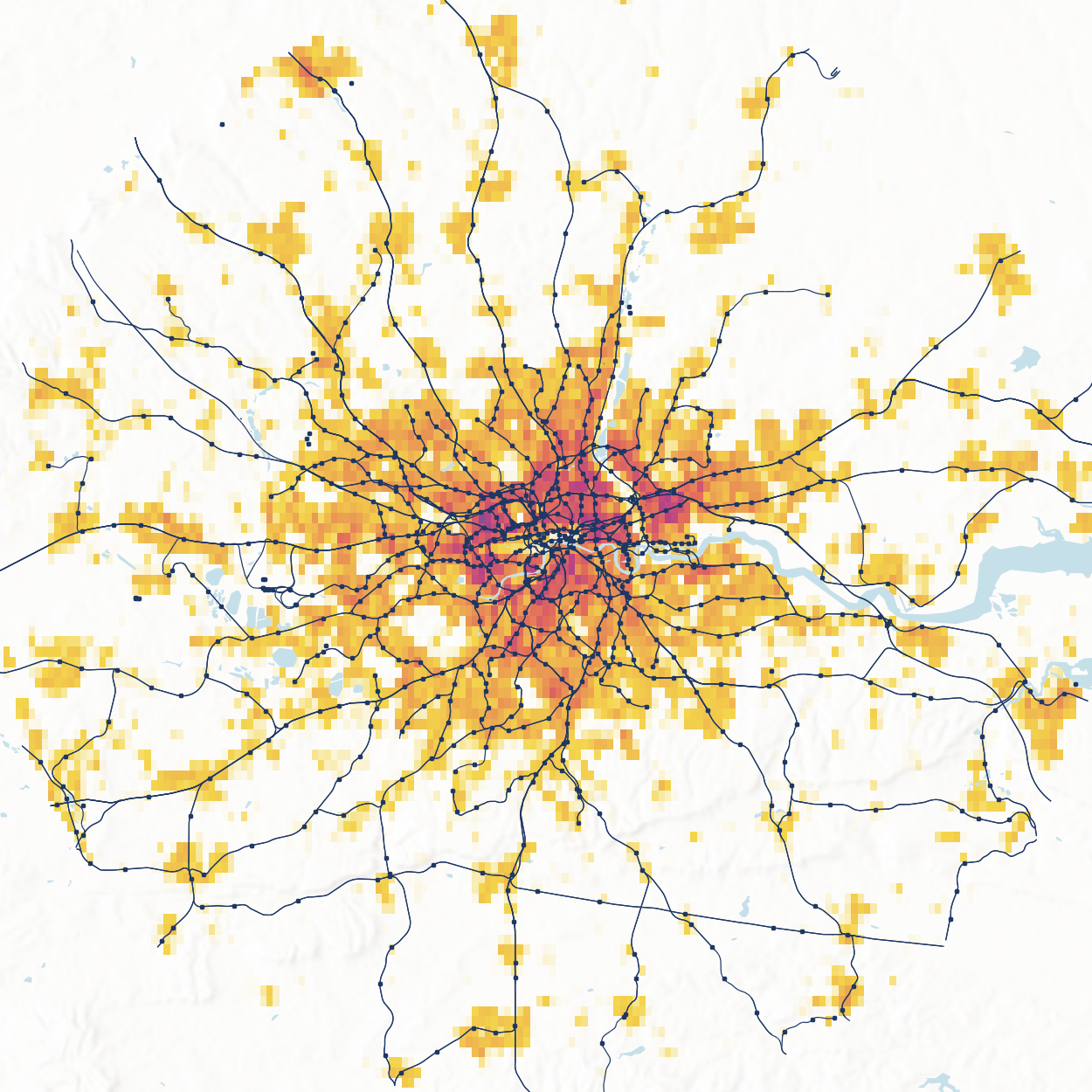

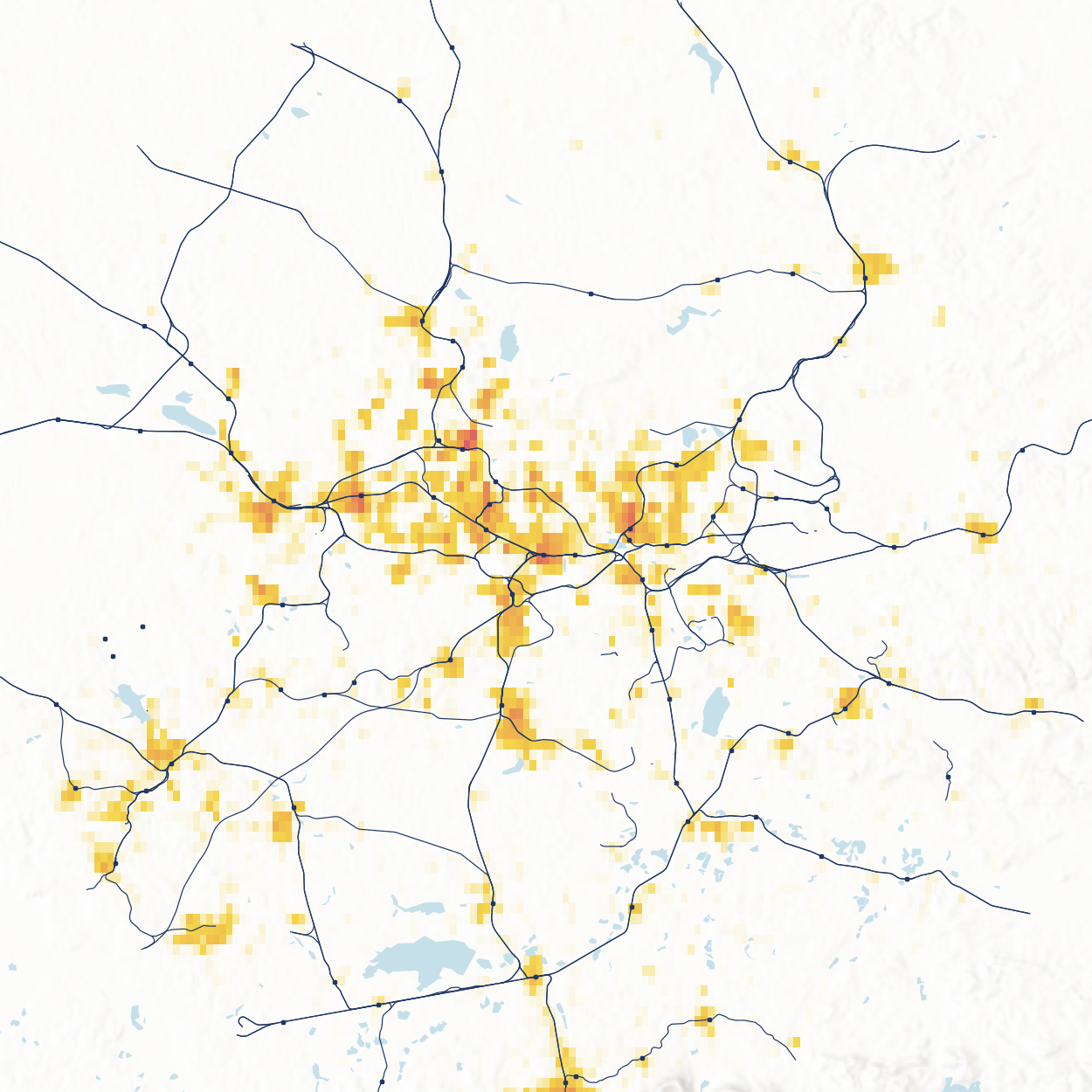

Good public transit connects people to places. Ideally, this is done efficiently and sustainably, with transit routes and stations serving and connecting the most amount of people possible. But in reality, there's a lot of variation within and between cities in how effectively this is done.

To look at this, we've created maps of major rail transit lines and stations (rapid transit, regional rail, LRT) overlaid onto population density for 250 of the most populated urban regions around the globe. Click the dropdowns below to view how well transit systems serve their populations in different cities.

Each map has the same geographic scale, 100km in diameter, to be easily comparable with each other.

Using these maps, we've also computed several metrics examining characteristics of transit oriented development, and ranked how well cities perform relative to each other. Generally, the greater the density and proportion of the population that lives near major rail transit, the better.

Population data for these maps are from GlobPOP, and rail transit data are from OpenStreetMap. At the bottom of this page we describe these data sources, our methodology, and limitations in more detail.

Rail transit line and station

Population density (people / km²)

14.13M

Urban population

3.44M

4,400

Urban population density (people / km²)

1,700

7,000

Population density in the area 1km from all major rail transit stations

2,200

63.0%

% of the urban population within 1km of a major rail transit station

16.2%

44.6%

% of the urban area within 1km of a major rail transit station

9.3%

1.41

Concentration ratio (% urban pop near transit / % urban area near transit)

1.74

City Rankings

Select by metric:

Select by region:

Data & Methods

Our list of cities came from a dataset from Natural Earth. We started with a list of the 300 most populated cities, but then manually removed cases where one city was essentially the suburb of another city at our scale (e.g. Howrah was removed since it is very close to Kolkata), as well as removed cities without any rail transit.

For each city, we then defined the urban region shown on the maps as a circle with a 50km radius from the centre point noted in the Natural Earth dataset. We chose to use a standard circle size for all regions to account for idiosyncrasies in how different parts of the world define metro areas. 50km is approximately the outer range that someone would commute to/from a city centre along a major rail corridor.

We sourced the population density data from GlobPOP which provides population count and density data at a spatial resolution of 30 arc-seconds (approximately 1km at the equator) around the globe. Our urban population density metrics are computed after removing areas where population density is less than 400km², to account for how regions vary in terms of how much agricultural land and un-habitable geography they have (e.g. mountains, water, etc. 400km² is the same threshold used by Statistics Canada to define populated places.

We downloaded rail and station data from OpenStreetMap (OSM) using overpass turbo with this query. We then calculated 1km buffers around each station and then estimated the population within the buffered area via aerial interpolation. OSM is crowd-sourced data, and while the quality and comprehensiveness of OSM data is quite good in most cities, there are several cities that have missing or incorrect data. If you see any errors, please update OSM! As OSM data is edited and improved, we'll aim to update our maps and metrics in the future.

There are two main limitations with this transit data: 1) it only includes rail transit, not Bus Rapid Transit (BRT), which in many cities provides comparable service to rail. 2) it does not account for frequency (i.e. headway) of routes. While many transit agencies share their routes and schedules in GTFS format, which includes information about frequency and often technology (bus, rail, etc.), we found that the availability of GTFS at a global scale was not available everywhere, particularly outside of Europe and North America.

Now of course, where people live is just one piece; the goal of transit is ultimately to take people where they want to go (work, school, recreation, etc.). It would be great to layer on employment and activity location data onto these maps to also look at the destination side of the equation as well as analyze connectivity of networks. Something to work on in the future!

---

More information about this project, code, data, etc. are available on GitHub.

Four billion years ago, Earth was a fiery, tumultuous world of molten rock, volcanic eruptions, and toxic skies, with searing heat and the constant threat of asteroid impacts.

Thankfully, our planet has cooled off a bit since then. Nevertheless, the Earth still radiates vast amounts of geothermal energy. It’s a clean, limitless, always-on power source lying beneath our feet — we just have to dig for it. Or get robots to do the hard work for us.

Borobotics, a startup from Switzerland, has developed an autonomous drilling machine — dubbed the “world’s most powerful worm” — that promises to make harnessing geothermal heat cheaper and more accessible for everyone.

“Drilling will become possible on properties where it would be unthinkable today — small gardens, parking lots, and potentially even basements,” Moritz Pill, Borobotics’ co-founder, tells TNW.

At just 13.5 cm wide and 2.8 metres long, the compact boring robot can silently burrow just about anywhere. It could make geothermal a viable backyard energy source.

The machine — nicknamed “Grabowski” after the famous cartoon mole — is the world’s first geothermal drill that operates autonomously, according to the startup. Sensors in Grabowski’s head mean it can detect which type of material it’s boring through. If it bumps into a water spring or gas reservoir on its way down, the robot worm automatically seals the borehole shut. And unlike the diesel-powered drills typical to the industry, the machine plugs into a regular electrical socket.

However, Grabowski’s humble frame has a few drawbacks. The device is less powerful than bigger rigs. It’s also slower and can only dig to a maximum depth of 500 metres. But for Borobotics’ target market, that’s more than adequate, it says.

Limitless heat just below our feet

While most geothermal startups look to produce utility-scale electricity by digging many kilometres below the Earth’s crust, Borobotics is going shallow.

“In many European countries, at a depth of 250 metres, you have an average temperature of 14 degrees C,” says Pill. “This is ideal for efficient heating in winter, while still being cold enough to cool the building in summer.”

Borobotics wants to tap the burgeoning demand for geothermal heat pumps. These devices use a network of subterranean pipes to transfer heat from below the ground to a building on the surface. Under the right conditions, they double-up as air conditioning.

Heating and cooling buildings accounts for half of global energy consumption, the lion’s share of which comes from burning fossil fuels like natural gas.

To curb emissions, the EU has committed to installing 43 million new heat pumps between 2023 and 2030, as part of the bloc’s €300bn REPowerEU plan.

The advantages are obvious. Heat pumps use electricity instead of fossil fuels to transfer heat or cold air. They are up to three times more efficient than the equivalent gas boiler. If they plug into a renewable energy source, even better.

The EU backs both geothermal and air-source heat pumps, but the latter dominate thanks to lower costs and easier installation. That’s despite geothermal heat pumps being more efficient because they rely on stable subterranean heat rather than fluctuating outdoor temperatures.

“The potential of geothermal heat pumps to decarbonise Europe is substantial, as long as the cost comes down,” Torsten Kolind, managing partner at Underground Ventures, tells TNW. “The minute that happens, the market is open.”

Underground Ventures, based in Copenhagen, is the world’s first VC dedicated entirely to funding geothermal tech startups. The firm led Borobotics’ CHF 1.3mn (€1.38mn) pre-seed funding round, announced this week.

Due to their small size, Borobotics says its drill is “very resource efficient” to produce and maintain. What’s more, Grabowski’s autonomous capabilities, other than being cool, have a hidden advantage.

Pill paints the following picture:

“A small team arrive to a site with a Sprinter van containing everything necessary to drill,” he explains. “They set the drill in half a day and from then on it works autonomously.”

Pill predicts that one or two people will be able to handle 10-13 drill sites simultaneously. If correct, this means drilling companies can cover more ground in less time, even if Grabowski is a little more sluggish than its fossil-fuelled relatives.

Given the EU’s chronic shortage of heat pump installers, an autonomous drilling robot may be a welcome helping hand.

Despite the apparent potential, it’s still early days for Borobotics. Founded in 2023, the company is currently developing its first working prototype. Fuelled by its first major pot of funding, it looks to test the robot in real conditions this year.

Geothermal tech is heating up

In December, the International Energy Agency (IEA) released its first report on geothermal energy in over 10 years. In the report, the IEA predicted that geothermal could cater to 15% of global energy demand by 2050, up from just 1% today.

Geothermal projects of old were largely state-led, and confined to volcanically active regions like Iceland or New Zealand where hot water bubbles at or near the surface. But the next wave of installations looks to be led by startups armed with state-of-the-art technology that allows them to dig deeper and more efficiently.

Geothermal energy startups attracted $650mn in VC funding in 2024, the highest value ever recorded, according to Dealroom data. One of those is US-based Fervo Energy, backed by Bill Gates’ Breakthrough Energy Ventures. Google has already plugged into Fervo’s geothermal plant in Nevada to power one of its data centres. Another upstart is Canada’s Eavor, which is currently building a giant underground “radiator” in Germany that could heat an entire town.

“The problem has always been geology and economics, but the advances of startups like Fervo and Eavor in recent years have changed the game,” says Kolind.

While US startups are leading the pack, Europe is well poised to compete.

“Europe has excellent geothermal subsurface conditions, and, unlike America, it also has a strong tradition for district heating,” says Kolind. The investor believes it’s only a matter of time before Europe’s investors and policymakers go all-in on geothermal tech.

“Unlike natural gas and coal, it is fossil-free. Unlike wind and solar, it is always-on. And unlike nuclear energy, it is geopolitically benign,” he says.