I. When precision becomes a distraction

Mike Berners-Lee of Small World Consulting recently set out Six Questions to Ask Your Carbon Accountant, a powerful call for methodological rigour in corporate emissions reporting. His questions focus on completeness, truncation error, Scope-3 integrity, aviation impacts and methodological transparency — the technical foundations of credible carbon accounting. They are necessary. But they are not sufficient.

Even perfect accounting cannot correct a deeper failure: we are valuing carbon at levels that make climate destruction economically rational. We now measure emissions with forensic precision while pricing them at levels that systematically instruct markets to continue destabilising the climate. The result is not better climate outcomes — it is the rigorous documentation of failure.

II. Carbon pricing is market infrastructure, not ESG decoration

Carbon pricing is not an Environmental, Social and Governance (ESG) metric. It is financial infrastructure — the switch that determines which projects receive capital, which business models survive, how sovereign and corporate risk is priced, and whether clean technologies clear investment hurdle rates.10, 17 When carbon is mispriced, markets are not merely inefficient — they are structurally miswired to produce the wrong outcomes.

The World Bank’s State and Trends of Carbon Pricing 2023 documents that carbon pricing instruments now cover roughly 23% of global emissions, with revenues exceeding $95 billion annually.17 Yet these instruments operate within a framework where prices remain systematically disconnected from the physical and economic realities of climate damage. Newell et al. (2014) demonstrate that carbon market design, stability, and reform are critical determinants of whether pricing mechanisms can achieve their intended environmental objectives — but design alone cannot compensate for fundamental undervaluation.10

If carbon is priced below its true social cost, financial institutions are systematically misclassifying climate risk — mispricing capital, understating transition exposure, and compounding systemic financial instability.

III. The valuation gap

The divergence between market prices and scientifically grounded damage estimates is substantial and systematic:

Voluntary carbon markets, which traded approximately 200 million tonnes of CO₂ equivalents in 2022, clear at prices ranging from $5 to $50 per tonne, with median prices well below $20.4, 15 These markets, despite their growth, operate primarily as mechanisms for optional corporate engagement rather than as price signals reflecting actual climate costs.

Regulated emissions trading systems — including the European Union Emissions Trading System (EU ETS) and the UK ETS — have seen prices rise to approximately €80–110 per tonne in recent years.17 While this represents significant progress from earlier price levels, these figures remain politically constrained and well below high-integrity academic estimates. Newell et al. (2014) note that political economy constraints systematically limit the stringency of cap-and-set mechanisms.10

Conventional social cost of carbon (SCC) estimates using standard integrated assessment models with 3% discount rates have historically ranged from $50–100 per tonne.11 Nordhaus’s widely cited work employs a damages function calibrated to conventional economic assumptions about future growth, technological change, and the monetary value of climate impacts.

Ethical SCC estimates that weight intergenerational equity more heavily — as advocated by Stern (2007) using near-zero pure time preference — yield valuations of $150–400+ per tonne. Stern’s framework rests on the ethical position that future generations’ welfare should not be discounted merely because they exist in the future, a stance supported by Arrow et al. (2013) in their analysis of determining benefits and costs for future generations.1, 14

SCC estimates incorporating tipping point risks range from $300–700+ per tonne. Cai et al. (2016) demonstrate that environmental tipping points — such as Arctic methane release, Amazon dieback, or Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation collapse — significantly affect cost-benefit assessments of climate policies.2 Dietz et al. (2021) extend this analysis by showing that economic impacts of tipping points in the climate system are non-linear and potentially catastrophic, fundamentally altering optimal policy responses.3

The most comprehensive recent meta-analysis by Rennert et al. (2022), published in Nature, synthesises updated climate science, economic modelling, and damage function research to argue that comprehensive evidence implies a substantially higher social cost of CO₂ — potentially exceeding $185 per tonne under central assumptions and rising to several hundred dollars when catastrophic risks are properly incorporated.13

High-integrity academic estimates, therefore, exceed prevailing market prices by factors of 5–20×. At current prices, destabilising the climate remains cheaper than protecting it.

IV. Why carbon’s “true cost” cannot be purely calculated

The social cost of carbon is not a single number — it depends on ethical choices that cannot be resolved through calculation alone. Arrow et al. (2013) emphasise that discount rate selection involves irreducible normative judgments about intergenerational equity.1 A 3% discount rate, commonly employed in policy analysis, implies that damages occurring 50 years hence are worth less than one-quarter of equivalent damages today — a position that may be economically conventional but is ethically contentious.14

Weitzman (2009) argues that conventional damage functions systematically underestimate the probability and impact of catastrophic climate outcomes. His analysis of “dismal theorem” scenarios — where the expected value of climate damages may be infinite due to fat-tailed distributions of catastrophic risk — challenges the entire framework of cost-benefit analysis as applied to existential threats. Pindyck (2013) reinforces this critique, noting that integrated assessment models rest on damage functions with limited empirical grounding, particularly at high temperatures where non-linear and threshold effects dominate.12, 16

The treatment of non-market values — species extinction, cultural heritage loss, forced displacement — further illustrates that carbon valuation embeds ethical positions disguised as mathematics. These are not technical parameters. They are moral choices about whose welfare counts and how much.

V. Why measurement alone cannot fix this

Consider two identical companies with identical emissions inventories of 10,000 tonnes CO₂e annually. Both have undertaken comprehensive Scope 1, 2, and 3 accounting. Both have verified their data to ISO 14064 standards. The measurement is identical. Yet the strategic implications diverge radically depending on carbon valuation:

• At $10/tonne: Annual cost = $100,000. Strategic signal: “immaterial cost; maintain business as usual.”

• At $300/tonne: Annual cost = $3,000,000. Strategic signal: “material existential risk; transform business model immediately.”

Valuation — not measurement — determines outcomes. This is why Rennert et al. (2022) and the International Energy Agency argue that carbon pricing levels, not merely accounting precision, are the critical determinant of whether investment flows align with 1.5°C pathways.7, 13

VI. Temperature is a stock problem, not a policy variable

Global mean temperature is governed primarily by atmospheric CO₂ concentration (measured in parts per million) — a stock variable, not a flow variable. Once emitted, CO₂ persists for centuries (IPCC, 2021). Each year of carbon undervaluation irreversibly ratchets the atmospheric stock upward. Nationally Determined Contributions (NDC) failure does not merely delay progress; it locks in future warming that no later policy correction can undo.

The IPCC’s Sixth Assessment Report (2021) confirms that warming is approximately linearly proportional to cumulative emissions, meaning that every tonne of CO₂ added to the atmosphere commits the planet to additional warming.6 Carbon mispricing, therefore, creates an irreversible physical ratchet with compounding fiscal and credit consequences.

VII. The sovereign debt time bomb

Stage 1: Undervaluation delays transition and locks in stranded assets

Pricing carbon at $10–50 instead of $200–400 creates three distinct market failures:

First, it delays the retirement of existing fossil infrastructure. While new renewable electricity generation is now cheaper than new fossil plants in most markets, low carbon prices make continued operation of existing fossil assets — with sunk capital costs already paid — appear economically rational even when incompatible with climate targets.7 Coal plants, gas infrastructure, and petrochemical facilities continue operating past their climate-compatible retirement dates because carbon externalities remain unpriced.

Second, it enables marginal new fossil investments that should not proceed. In hard-to-abate sectors — heavy industry, long-haul aviation, maritime shipping, and certain industrial processes — clean alternatives remain more expensive than incumbent fossil technologies. Low carbon prices systematically bias investment decisions toward fossil lock-in in precisely those sectors where technological transformation is most urgent but economically challenging.

Third, it misdirects capital flows. The IEA’s Net Zero Roadmap demonstrates that achieving 1.5°C pathways requires carbon prices to reach $130–250 by 2030 in advanced economies — levels far exceeding current market realities.7 When carbon is underpriced, private capital systematically flows to high-carbon activities that maximise short-term returns while accumulating long-term climate liabilities. Paris Agreement targets become structurally unachievable when price signals are systematically inverted.

Stage 2: NDC failure becomes physical damage

If current policies continue rather than meeting NDC commitments, projected warming rises from 2.0–2.4°C to 2.7–3.0°C by 2100.6 Howard and Sterner’s (2017) meta-analysis of climate damage estimates demonstrates that each additional 0.5°C of warming pushes economies into non-linear damage regimes where losses accelerate.5 Extreme weather events increase in frequency and intensity by factors of 4–6× rather than 2–3×, forced climate migration potentially escalates from 50–100 million to 200–300 million people, and annual adaptation costs double from $140–300 billion to $280–500 billion globally.

Stage 3: Climate damage erodes fiscal capacity

Climate impacts manifest as disaster reconstruction costs, agricultural collapse, tourism decline, health system strain, and forced migration — each of which suppresses GDP, erodes tax revenues, and strains government budgets.5 The asymmetry is brutal: the most climate-vulnerable states face the highest damage and the least fiscal buffer.

Stage 4: Credit downgrades create debt spirals

Climate damage reduces economic growth, which increases fiscal stress, which triggers sovereign credit downgrades. Each ratings notch downgrade typically adds 50–100 basis points to borrowing costs, which increases debt service burdens, which reduces adaptation capacity, which intensifies climate damage, which prompts further downgrades.18 This self-reinforcing debt-climate doom loop is already visible in multiple small island developing states and climate-vulnerable economies. The International Monetary Fund warns that 50–60 emerging markets face heightened climate-related credit risk by 2030.

VIII. Transition risk: Cheap carbon today guarantees violent adjustment tomorrow

Delayed carbon pricing does not avoid economic disruption — it amplifies it.3,7 Honest pricing implemented now permits gradual 40-year capital reallocation as assets naturally depreciate. Delayed pricing necessitates compressed 15-year crash programmes characterised by stranded assets, credit events, and sovereign stress.

The mechanism is straightforward: cheap carbon today encourages continued investment in long-lived fossil infrastructure. When climate damages escalate, or policy finally tightens, that infrastructure becomes economically worthless overnight — stranding trillions in capital and triggering cascading financial instability. Lenton et al. (2019) emphasise that crossing climate tipping points imposes discontinuous regime shifts that cannot be smoothly navigated through incremental policy adjustments.8

IX. The missing seventh question

Berners-Lee’s six questions discipline measurement. The decisive question is:

What value are you placing on carbon — and what ethical framework does it embed?

If the answer is “$10-$20/tonne because that’s what the market charges,” your accounting is methodologically sound — and systemically lethal. Forest Research (2023) confirms that prevailing market prices reflect political economy constraints and voluntary market dynamics rather than defensible estimates of climate damage.4 Pindyck (2013) and Weitzman (2009) demonstrate that conventional economic models systematically underestimate catastrophic risk, embedding ethical assumptions that privilege present consumption over future survival.12, 16

X. Counter-arguments — answered

“High carbon prices kill growth.” Growth models that predict negative impacts from carbon pricing typically assume static technology and ignore cost curves. Yet renewable energy LCOE (levelised cost of energy) has fallen below fossil alternatives in most markets without carbon pricing, and high carbon prices accelerate this technological disruption.7 Moreover, carbon pricing can be growth-neutral or growth-positive when revenues are recycled into productive investment, R&D support, or tax relief that reduces distortionary taxation elsewhere.17 The real growth killer is unpriced climate damage.

“Developing countries can’t afford high carbon prices.” Developing economies suffer most from carbon undervaluation. Climate damage costs substantially exceed carbon pricing costs in climate-vulnerable regions.5 The alternative to high carbon prices is not fiscal stability — it is sovereign debt spirals triggered by escalating climate impacts that destroy tax bases, tourism revenues, agricultural productivity, and creditworthiness. High carbon prices, when coupled with border adjustments and climate finance transfers, protect developing economies from imported climate risk while preserving fiscal sovereignty.

“Use marginal abatement cost (MAC), not social cost of carbon.” This conflates two distinct concepts. MAC measures the cost of reducing emissions — how expensive it is to cut a tonne. SCC measures the cost of not reducing emissions — how much damage that tonne causes. Confusing them is a category error that systematically undervalues climate action by ignoring the avoided damages.9 Rational policy requires both: MAC informs how to abate efficiently; SCC informs how much abatement is justified.

XI. What must change: Specific levers

The path forward requires institutional reforms that make carbon valuation transparent, auditable, and defensible:

• ISSB/TCFD Phase 2 disclosure requirements: Mandate disclosure of internal carbon price assumptions alongside high-integrity benchmarks.3,13 Require narrative explanation when internal prices fall below scientifically grounded ranges.

• EU Taxonomy and sustainable finance frameworks: Require ethical-framework justification for carbon prices below €100/tonne in investment and lending decisions. Make carbon price assumptions a mandatory disclosure element for “sustainable” classification.

• Central bank stress testing: Incorporate carbon-price shock scenarios (e.g., sudden implementation of $200/tonne pricing) into financial stability assessments to expose transition risk concentrations and identify institutions with concentrated exposure to stranded asset risk.

• Credit rating agency methodology disclosure: Require agencies to disclose carbon price assumptions embedded in sovereign and corporate ratings, particularly for climate-vulnerable issuers. Ratings should explicitly incorporate transition risk from policy tightening.

• Asset manager stewardship codes: Establish voting expectations against boards employing carbon prices below €100/tonne without robust methodological and ethical justification. Link fiduciary duty to climate risk assessment.

These reforms would not dictate a single “correct” carbon price — ethical pluralism permits legitimate disagreement about discount rates and risk tolerance — but they would force transparency about the values embedded in current practice. Arrow et al. (2013) and the National Academies (2017) emphasise that making ethical assumptions explicit is a prerequisite for democratic accountability in climate policy.1,9

XII. Conclusion

Carbon accounting is not an ESG reporting exercise. It is the financial system infrastructure. When carbon is undervalued, Nationally Determined Contributions fail, temperature targets overshoot, sovereign balance sheets destabilise, and debt crises propagate.3, 18 We are not merely measuring our way to climate collapse. We are accounting our way into the next global sovereign debt crisis.

And the hinge on which it turns is the missing seventh question: not how precisely have you measured your emissions, but what value have you placed on carbon, and can you defend it?

Without honest carbon valuation, forensic emissions accounting becomes an elaborate ritual of organised irresponsibility — documenting, with ever-increasing precision, our collective failure to price the most consequential market externality in human history.

illuminem Voices is a democratic space presenting the thoughts and opinions of leading Sustainability & Energy writers, their opinions do not necessarily represent those of illuminem.

See how the companies in your sector perform on sustainability. On illuminem’s Data Hub™, access emissions data, ESG performance, and climate commitments for thousands of industrial players across the globe.

References

1. Arrow, K. J., Cropper, M. L., Gollier, C., Groom, B., Heal, G. M., Newell, R. G., … Weitzman, M. L. (2013). Determining benefits and costs for future generations. Science, 341(6144), 349–350.

2. Cai, Y., Judd, K. L., Lenton, T. M., Lontzek, T. S., & Narita, D. (2016). Environmental tipping points significantly affect the cost–benefit assessment of climate policies. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 113(15), 4106–4111.

3. Dietz, S., Rising, J., Stoerk, T., & Wagner, G. (2021). Economic impacts of tipping points in the climate system. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 118(34), e2103081118.

4. Forest Research. (2023). Review of approaches to carbon valuation, discounting and risk management. UK Government.

5. Howard, P. H., & Sterner, T. (2017). Few and not so far between: A meta-analysis of climate damage estimates. Environmental and Resource Economics, 68, 197–225.

6. Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). (2021). AR6 Working Group I: The Physical Science Basis. Cambridge University Press.

7. International Energy Agency (IEA). (2023). Net Zero Roadmap: A Global Pathway to Keep the 1.5 °C Goal in Reach.

8. Lenton, T. M., et al. (2019). Climate tipping points—too risky to bet against. Nature, 575, 592–595.

9. National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. (2017). Valuing climate damages: Updating estimation of the social cost of carbon dioxide. National Academies Press.

10. Newell, R. G., Pizer, W. A., & Raimi, D. (2014). Carbon market design, stability, and reform. Energy Policy, 75, 22–31.

11. Nordhaus, W. (2017). Revisiting the social cost of carbon. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 114(7), 1518–1523.

12. Pindyck, R. S. (2013). Climate change policy: What do the models tell us? Journal of Economic Literature, 51(3), 860–872.

13. Rennert, K., et al. (2022). Comprehensive evidence implies a higher social cost of CO₂. Nature, 610, 687–692.

14. Stern, N. (2007). The economics of climate change: The Stern Review. Cambridge University Press.

15. Trove Research. (2023). State of the voluntary carbon market.

16. Weitzman, M. L. (2009). On modeling and interpreting the economics of catastrophic climate change. Review of Economics and Statistics, 91(1), 1–19.

17. World Bank. (2023). State and Trends of Carbon Pricing 2023.

18. World Bank. (2024). Carbon Pricing Dashboard.

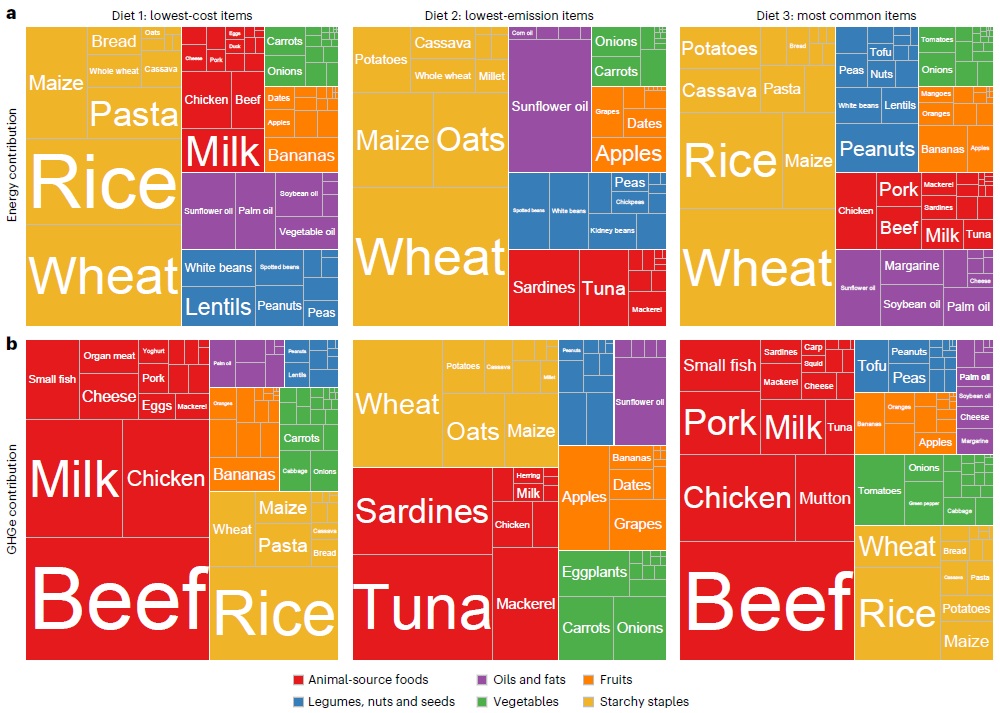

Energy (top) and emissions (bottom) contributions from different food groups within the three diets modelled by the study. Each column represents a different diet (left to right): lowest-cost, lowest-emission and most common items. The boxes are coloured by food group: animal-sourced foods (red), legumes, nuts and seeds (blue), oils and fats (purple), vegetables (green), fruits (orange) and starchy staples (yellow). Source: Bai et al. (

Energy (top) and emissions (bottom) contributions from different food groups within the three diets modelled by the study. Each column represents a different diet (left to right): lowest-cost, lowest-emission and most common items. The boxes are coloured by food group: animal-sourced foods (red), legumes, nuts and seeds (blue), oils and fats (purple), vegetables (green), fruits (orange) and starchy staples (yellow). Source: Bai et al. (