I am a science-fiction writer, which means that my job is to make up futuristic parables about our current techno-social arrangements to interrogate not just what a gadget does, but who it does it for, and who it does it to.

What I do not do is predict the future. No one can predict the future, which is a good thing, since if the future were predictable, that would mean we couldn’t change it.

Now, not everyone understands the distinction. They think science-fiction writers are oracles. Even some of my colleagues labor under the delusion that we can “see the future”.

Then there are science-fiction fans who believe that they are reading the future. A depressing number of those people appear to have become AI bros. These guys can’t shut up about the day that their spicy autocomplete machine will wake up and turn us all into paperclips has led many confused journalists and conference organizers to try to get me to comment on the future of AI.

That’s something I used to strenuously resist doing, because I wasted two years of my life explaining patiently and repeatedly why I thought crypto was stupid, and getting relentlessly bollocked by cryptocurrency cultists who at first insisted that I just didn’t understand crypto. And then, when I made it clear that I did understand crypto, they insisted that I must be a paid shill.

This is literally what happens when you argue with Scientologists, and life is just too short. That said, people would not stop asking – so I’m going to explain what I think about AI and how to be a good AI critic. By which I mean: “How to be a critic whose criticism inflicts maximum damage on the parts of AI that are doing the most harm.”

An army of reverse centaurs

In automation theory, a “centaur” is a person who is assisted by a machine. Driving a car makes you a centaur, and so does using autocomplete.

A reverse centaur is a machine head on a human body, a person who is serving as a squishy meat appendage for an uncaring machine.

For example, an Amazon delivery driver, who sits in a cabin surrounded by AI cameras that monitor the driver’s eyes and take points off if the driver looks in a proscribed direction, and monitors the driver’s mouth because singing is not allowed on the job, and rats the driver out to the boss if they do not make quota.

The driver is in that van because the van cannot drive itself and cannot get a parcel from the curb to your porch. The driver is a peripheral for a van, and the van drives the driver, at superhuman speed, demanding superhuman endurance.

Obviously, it’s nice to be a centaur, and it’s horrible to be a reverse centaur. There are lots of AI tools that are potentially very centaurlike, but my thesis is that these tools are created and funded for the express purpose of creating reverse centaurs, which none of us want to be.

But like I said, the job of a science-fiction writer is to do more than think about what the gadget does, and drill down on who the gadget does it for and who the gadget does it to. Tech bosses want us to believe that there is only one way a technology can be used. Mark Zuckerberg wants you to think that it is technologically impossible to have a conversation with a friend without him listening in. Tim Cook wants you to think that it is impossible for you to have a reliable computing experience unless he gets a veto over which software you install and without him taking 30 cents out of every dollar you spend. Sundar Pichai wants you to think that it is for you to find a webpage unless he gets to spy on you from asshole to appetite.

This is all a kind of vulgar Thatcherism. Margaret Thatcher’s mantra was: “There is no alternative.” She repeated this so often they called her “Tina” Thatcher: There. Is. No. Alternative.

“There is no alternative” is a cheap rhetorical slight. It’s a demand dressed up as an observation. “There is no alternative” means: “stop trying to think of an alternative.”

I’m a science-fiction writer – my job is to think of a dozen alternatives before breakfast.

So let me explain what I think is going on here with this AI bubble and who the reverse-centaur army is serving, and sort out the bullshit from the material reality.

Start with monopolies: tech companies are gigantic and they don’t compete, they just take over whole sectors, either on their own or in cartels.

Google and Meta control the ad market. Google and Apple control the mobile market, and Google pays Apple more than $20bn a year not to make a competing search engine, and of course, Google has a 90% search market share.

Now, you would think that this was good news for the tech companies, owning their whole sector.

But it’s actually a crisis. You see, when a company is growing, it is a “growth stock”, and investors really like growth stocks. When you buy a share in a growth stock, you are making a bet that it will continue to grow. So growth stocks trade at a huge multiple of their earnings. This is called the “price to earnings ratio” or “PE ratio”.

But once a company stops growing, it is a “mature” stock, and it trades at a much lower PE ratio. So for every dollar that Target – a mature company – brings in, it is worth $10. It has a PE ratio of 10, while Amazon has a PE ratio of 36, which means that for every dollar Amazon brings in, the market values it at $36.

It’s wonderful to run a company that has a growth stock. Your shares are as good as money. If you want to buy another company or hire a key worker, you can offer stock instead of cash. And stock is very easy for companies to get, because shares are manufactured right there on the premises, all you have to do is type some zeros into a spreadsheet, while dollars are much harder to come by. A company can only get dollars from customers or creditors.

So when Amazon bids against Target for a key acquisition or a key hire, Amazon can bid with shares they make by typing zeros into a spreadsheet, and Target can only bid with dollars they get from selling stuff to us or taking out loans, which is why Amazon generally wins those bidding wars.

That’s the upside of having a growth stock. But here is the downside: eventually a company has to stop growing. Like, say you get a 90% market share in your sector, how are you going to grow?

If you are an exec at a dominant company with a growth stock, you have to live in constant fear that the market will decide that you are not likely to grow any further. Think of what happened to Facebook in the first quarter of 2022. They told investors that they experienced slightly slower growth in the US than they had anticipated, and investors panicked. They staged a one-day, $240bn sell-off. A quarter-trillion dollars in 24 hours! At the time, it was the largest, most precipitous drop in corporate valuation in human history.

That’s a monopolist’s worst nightmare, because once you’re presiding over a “mature” firm, the key employees you have been compensating with stock experience a precipitous pay drop and bolt for the exits, so you lose the people who might help you grow again, and you can only hire their replacements with dollars – not shares.

This is the paradox of the growth stock. While you are growing to domination, the market loves you, but once you achieve dominance, the market lops 75% or more off your value in a single stroke if they do not trust your pricing power.

Which is why growth-stock companies are always desperately pumping up one bubble or another, spending billions to hype the pivot to video or cryptocurrency or NFTs or the metaverse or AI.

I am not saying that tech bosses are making bets they do not plan on winning. But winning the bet – creating a viable metaverse – is the secondary goal. The primary goal is to keep the market convinced that your company will continue to grow, and to remain convinced until the next bubble comes along.

So this is why they’re hyping AI: the material basis for the hundreds of billions in AI investment.

Now I want to talk about how they’re selling AI. The growth narrative of AI is that AI will disrupt labor markets. I use “disrupt” here in its most disreputable tech-bro sense.

The promise of AI – the promise AI companies make to investors – is that there will be AI that can do your job, and when your boss fires you and replaces you with AI, he will keep half of your salary for himself and give the other half to the AI company.

That is the $13tn growth story that Morgan Stanley is telling. It’s why big investors are giving AI companies hundreds of billions of dollars. And because they are piling in, normies are also getting sucked in, risking their retirement savings and their family’s financial security.

Now, if AI could do your job, this would still be a problem. We would have to figure out what to do with all these unemployed people.

But AI can’t do your job. It can help you do your job, but that does not mean it is going to save anyone money.

Take radiology: there is some evidence that AI can sometimes identify solid-mass tumors that some radiologists miss. Look, I’ve got cancer. Thankfully, it’s very treatable, but I’ve got an interest in radiology being as reliable and accurate as possible.

Let’s say my hospital bought some AI radiology tools and told its radiologists: “Hey folks, here’s the deal. Today, you’re processing about 100 X-rays per day. From now on, we’re going to get an instantaneous second opinion from the AI, and if the AI thinks you’ve missed a tumor, we want you to go back and have another look, even if that means you’re only processing 98 X-rays per day. That’s fine, we just care about finding all those tumors.”

If that’s what they said, I’d be delighted. But no one is investing hundreds of billions in AI companies because they think AI will make radiology more expensive, not even if that also makes radiology more accurate. The market’s bet on AI is that an AI salesman will visit the CEO of Kaiser and make this pitch: “Look, you fire nine out of 10 of your radiologists, saving $20m a year. You give us $10m a year, and you net $10m a year, and the remaining radiologists’ job will be to oversee the diagnoses the AI makes at superhuman speed – and somehow remain vigilant as they do so, despite the fact that the AI is usually right, except when it’s catastrophically wrong.

“And if the AI misses a tumor, this will be the human radiologist’s fault, because they are the ‘human in the loop’. It’s their signature on the diagnosis.”

This is a reverse centaur, and it is a specific kind of reverse centaur: it is what Dan Davies calls an “accountability sink”. The radiologist’s job is not really to oversee the AI’s work, it is to take the blame for the AI’s mistakes.

This is another key to understanding – and thus deflating – the AI bubble. The AI can’t do your job, but an AI salesman can convince your boss to fire you and replace you with an AI that can’t do your job. This is key because it helps us build the kinds of coalitions that will be successful in the fight against the AI bubble.

If you are someone who is worried about cancer, and you are being told that the price of making radiology too cheap to meter, is that we are going to have to rehouse America’s 32,000 radiologists, with the trade-off that no one will ever be denied radiology services again, you might say: “Well, OK, I’m sorry for those radiologists, and I fully support getting them job training or UBI or whatever. But the point of radiology is to fight cancer, not to pay radiologists, so I know what side I’m on.”

AI hucksters and their customers in the C-suites want the public on their side. They want to forge a class alliance between AI deployers and the people who enjoy the fruits of the reverse centaurs’ labor. They want us to think of ourselves as enemies to the workers.

Now, some people will be on the workers’ side because of politics or aesthetics. But if you want to win over all the people who benefit from your labor, you need to understand and stress how the products of the AI will be substandard. That they are going to get charged more for worse things. That they have a shared material interest with you.

Will those products be substandard? There is every reason to think so.

Think of AI software generation: there are plenty of coders who love using AI. Using AI for simple tasks can genuinely make them more efficient and give them more time to do the fun part of coding, namely, solving really gnarly, abstract puzzles. But when you listen to business leaders talk about their AI plans for coders, it’s clear they are not hoping to make some centaurs.

They want to fire a lot of tech workers – 500,000 over the past three years – and make the rest pick up their work with coding, which is only possible if you let the AI do all the gnarly, creative problem solving, and then you do the most boring, soul-crushing part of the job: reviewing the AI’s code.

And because AI is just a word-guessing program, because all it does is calculate the most probable word to go next, the errors it makes are especially subtle and hard to spot, because these bugs are nearly indistinguishable from working code.

For example: programmers routinely use standard “code libraries” to handle routine tasks. Say you want your program to slurp in a document and make some kind of sense of it – find all the addresses, say, or all the credit card numbers. Rather than writing a program to break down a document into its constituent parts, you’ll just grab a library that does it for you.

These libraries come in families, and they have predictable names. If it’s a library for pulling in an html file, it might be called something like lib.html.text.parsing; and if it’s a for docx file, it’ll be lib.docx.text.parsing.

But reality is messy, humans are inattentive and stuff goes wrong, so sometimes, there will be another library, say, one for parsing pdfs, and instead of being called lib.pdf.text.parsing, it’s called lib.text.pdf.parsing. Someone just entered an incorrect library name and it stuck. Like I said, the world is messy.

Now, AI is a statistical inference engine. All it can do is predict what word will come next based on all the words that have been typed in the past. That means that it will “hallucinate” a library called lib.pdf.text.parsing, because that matches the pattern it’s already seen. And the thing is, malicious hackers know that the AI will make this error, so they will go out and create a library with the predictable, hallucinated name, and that library will get automatically sucked into the AI’s program, and it will do things like steal user data or try to penetrate other computers on the same network.

And you, the human in the loop – the reverse centaur – you have to spot this subtle, hard-to-find error, this bug that is indistinguishable from correct code. Now, maybe a senior coder could catch this, because they have been around the block a few times, and they know about this tripwire.

But guess who tech bosses want to preferentially fire and replace with AI? Senior coders. Those mouthy, entitled, extremely highly paid workers, who don’t think of themselves as workers. Who see themselves as founders in waiting, peers of the company’s top management. The kind of coder who would lead a walkout over the company building drone-targeting systems for the Pentagon, which cost Google $10bn in 2018.

For AI to be valuable, it has to replace high-wage workers, and those are precisely the workers who might spot some of those statistically camouflaged AI errors.

If you can replace coders with AI, who can’t you replace with AI? Firing coders is an ad for AI.

Which brings me to AI art – or “art” – which is often used as an ad for AI, even though it is not part of AI’s business model.

Let me explain: on average, illustrators do not make any money. They are already one of the most immiserated, precarious groups of workers out there. If AI image-generators put every illustrator working today out of a job, the resulting wage-bill savings would be undetectable as a proportion of all the costs associated with training and operating image-generators. The total wage bill for commercial illustrators is less than the kombucha bill for the company cafeteria at just one of OpenAI’s campuses.

The purpose of AI art – and the story of AI art as a death knell for artists – is to convince the broad public that AI is amazing and will do amazing things. It is to create buzz. Which is not to say that it is not disgusting that former OpenAI CTO Mira Murati told a conference audience that “some creative jobs shouldn’t have been there in the first place”.

It’s supposed to be disgusting. It’s supposed to get artists to run around and say: “The AI can do my job, and it’s going to steal my job, and isn’t that terrible?“

But can AI do an illustrator’s job? Or any artist’s job?

Let’s think about that for a second. I have been a working artist since I was 17 years old, when I sold my first short story. Here’s what I think art is: it starts with an artist, who has some vast, complex, numinous, irreducible feeling in their mind. And the artist infuses that feeling into some artistic medium. They make a song, a poem, a painting, a drawing, a dance, a book or a photograph. And the idea is, when you experience this work, a facsimile of the big, numinous, irreducible feeling will materialize in your mind.

But the image-generation program does not know anything about your big, numinous, irreducible feeling. The only thing it knows is whatever you put into your prompt, and those few sentences are diluted across a million pixels or a hundred-thousand words, so that the average communicative density of the resulting work is indistinguishable from zero.

It is possible to infuse more communicative intent into a work: writing more detailed prompts, or doing the selective work of choosing from among many variants, or directly tinkering with the AI image after the fact, with a paintbrush or Photoshop or the Gimp. And if there will ever be a piece of AI art that is good art – as opposed to merely striking, interesting or an example of good draftsmanship – it will be thanks to those additional infusions of creative intent by a human.

And in the meantime, it’s bad art. It’s bad art in the sense of being “eerie”, the word that cultural theorist Mark Fisher used to describe “when there is something present where there should be nothing, or there is nothing present when there should be something”.

AI art is eerie because it seems like there is an intender and an intention behind every word and every pixel, because we have a lifetime of experience that tells us that paintings have painters, and writing has writers. But it is missing something. It has nothing to say, or whatever it has to say is so diluted that it is undetectable.

Expanding copyright is not the answer

We should not simply shrug our shoulders and accept Thatcherism’s fatalism: “There is no alternative.”

So what is the alternative? A lot of artists and their allies think they have an answer: they say we should extend copyright to cover the activities associated with training a model.

And I am here to tell you they are wrong. Wrong because this would represent a massive expansion of copyright over activities that are currently permitted – for good reason. I’ll explain:

AI training involves scraping a bunch of webpages, which is unambiguously legal under present copyright law. Next, you perform analysis on those works. Basically, you count stuff on them: count pixels and their colors and proximity to other pixels; or count words. This is obviously not something you need a license for.

And after you count all the pixels or the words, it is time for the final step: publishing them. Because that is what a model is: a literary work (that is, a piece of software) that embodies a bunch of facts about a bunch of other works, word and pixel distribution information, encoded in a multidimensional array.

And again, copyright absolutely does not prohibit you from publishing facts about copyrighted works. And again, no one should want to live in a world where someone else gets to decide which factual statements you can publish.

But hey, maybe you think this is all sophistry. Maybe you think I’m full of shit. That’s fine. It wouldn’t be the first time someone thought that.

After all, even if I’m right about how copyright works now, there’s no reason we couldn’t change copyright to ban training activities, and maybe there’s even a clever way to wordsmith the law so that it only catches bad things we don’t like, and not all the good stuff that comes from scraping, analyzing and publishing – such as search engines and academic scholarship.

Well, even then, you’re not gonna help out creators by creating this new copyright. We have monotonically expanded copyright since 1976, so that today, copyright covers more kinds of works, grants exclusive rights over more uses, and lasts longer.

And today, the media industry is larger and more profitable than it has ever been, and also – the share of media industry income that goes to creative workers is lower than it has ever been, both in real terms, and as a proportion of those incredible gains made by creators’ bosses at the media company.

In a creative market dominated by five publishers, four studios, three labels, two mobile app stores, and a single company that controls all the ebooks and audiobooks, giving a creative worker extra rights to bargain with is like giving your bullied kid more lunch money.

It doesn’t matter how much lunch money you give the kid, the bullies will take it all. Give that kid enough money and the bullies will hire an agency to run a global campaign proclaiming: “Think of the hungry kids! Give them more lunch money!”

Creative workers who cheer on lawsuits by the big studios and labels need to remember the first rule of class warfare: things that are good for your boss are rarely what’s good for you.

A new copyright to train models will not get us a world where models are not used to destroy artists, it will just get us a world where the standard contracts of the handful of companies that control all creative labor markets are updated to require us to hand over those new training rights to those companies. Demanding a new copyright just makes you a useful idiot for your boss.

When really what they’re demanding is a world where 30% of the investment capital of the AI companies go into their shareholders’ pockets. When an artist is being devoured by rapacious monopolies, does it matter how they divvy up the meal?

We need to protect artists from AI predation, not just create a new way for artists to be mad about their impoverishment.

Incredibly enough, there is a really simple way to do that. After more than 20 years of being consistently wrong and terrible for artists’ rights, the US Copyright Office has finally done something gloriously, wonderfully right. All through this AI bubble, the Copyright Office has maintained – correctly – that AI-generated works cannot be copyrighted, because copyright is exclusively for humans. That is why the “monkey selfie” is in the public domain. Copyright is only awarded to works of human creative expression that are fixed in a tangible medium.

And not only has the Copyright Office taken this position, they have defended it vigorously in court, repeatedly winning judgments to uphold this principle.

The fact that every AI-created work is in the public domain means that if Getty or Disney or Universal or Hearst newspapers use AI to generate works – then anyone else can take those works, copy them, sell them or give them away for nothing. And the only thing those companies hate more than paying creative workers, is having other people take their stuff without permission.

The US Copyright Office’s position means that the only way these companies can get a copyright is to pay humans to do creative work. This is a recipe for centaurhood. If you are a visual artist or writer who uses prompts to come up with ideas or variations, that’s no problem, because the ultimate work comes from you. And if you are a video editor who uses deepfakes to change the eyelines of 200 extras in a crowd scene, then sure, those eyeballs are in the public domain, but the movie stays copyrighted.

But creative workers do not have to rely on the US government to rescue us from AI predators. We can do it ourselves, the way the writers did in their historic writers’ strike. The writers brought the studios to their knees. They did it because they are organized and solidaristic, but also are allowed to do something that virtually no other workers are allowed to do: they can engage in “sectoral bargaining”, whereby all the workers in a sector can negotiate a contract with every employer in the sector.

That has been illegal for most workers since the late 1940s, when the Taft-Hartley Act outlawed it. If we are gonna campaign to get a new law passed in hopes of making more money and having more control over our labor, we should campaign to restore sectoral bargaining, not to expand copyright.

AI is a bubble and bubbles are terrible.

Bubbles transfer the life savings of normal people who are just trying to have a dignified retirement to the wealthiest and most unethical people in our society, and every bubble eventually bursts, taking their savings with it.

But not every bubble is created equal. Some bubbles leave behind something productive. Worldcom stole billions from everyday people by defrauding them about orders for fiber optic cables. The CEO went to prison and died there. But the fiber outlived him. It’s still in the ground. At my home, I’ve got 2gb symmetrical fiber, because AT&T lit up some of that old Worldcom dark fiber.

It would have been better if Worldcom had not ever existed, but the only thing worse than Worldcom committing all that ghastly fraud would be if there was nothing to salvage from the wreckage.

I do not think we will salvage much from cryptocurrency, for example. When crypto dies, what it will leave behind is bad Austrian economics and worse monkey jpegs.

AI is a bubble and it will burst. Most of the companies will fail. Most of the datacenters will be shuttered or sold for parts. So what will be left behind?

We will have a bunch of coders who are really good at applied statistics. We will have a lot of cheap GPUs, which will be good news for, say, effects artists and climate scientists, who will be able to buy that critical hardware at pennies on the dollar. And we will have the open-source models that run on commodity hardware, AI tools that can do a lot of useful stuff, like transcribing audio and video; describing images; summarizing documents; and automating a lot of labor-intensive graphic editing – such as removing backgrounds or airbrushing passersby out of photos. These will run on our laptops and phones, and open-source hackers will find ways to push them to do things their makers never dreamed of.

If there had never been an AI bubble, if all this stuff arose merely because computer scientists and product managers noodled around for a few years coming up with cool new apps, most people would have been pleasantly surprised with these interesting new things their computers could do. We would call them “plugins”.

It’s the bubble that sucks, not these applications. The bubble doesn’t want cheap useful things. It wants expensive, “disruptive” things: big foundation models that lose billions of dollars every year.

When the AI-investment mania halts, most of those models are going to disappear, because it just won’t be economical to keep the datacenters running. As Stein’s law has it: “Anything that can’t go on forever eventually stops.”

The collapse of the AI bubble is going to be ugly. Seven AI companies currently account for more than a third of the stock market, and they endlessly pass around the same $100bn IOU.

AI is the asbestos in the walls of our technological society, stuffed there with wild abandon by a finance sector and tech monopolists run amok. We will be excavating it for a generation or more.

To pop the bubble, we have to hammer on the forces that created the bubble: the myth that AI can do your job, especially if you get high wages that your boss can claw back; the understanding that growth companies need a succession of ever more outlandish bubbles to stay alive; the fact that workers and the public they serve are on one side of this fight, and bosses and their investors are on the other side.

Because the AI bubble really is very bad news, it’s worth fighting seriously, and a serious fight against AI strikes at its roots: the material factors fueling the hundreds of billions in wasted capital that are being spent to put us all on the breadline and fill all our walls with hi-tech asbestos.

-

Cory Doctorow is a science fiction author, activist and journalist. He is the author of dozens of books, most recently Enshittification: Why Everything Suddenly Got Worse and What To Do About It. This essay was adapted from a recent lecture about his forthcoming book, The Reverse Centaur’s Guide to Life After AI, which is out in June

-

Spot illustrations by Brian Scagnelli

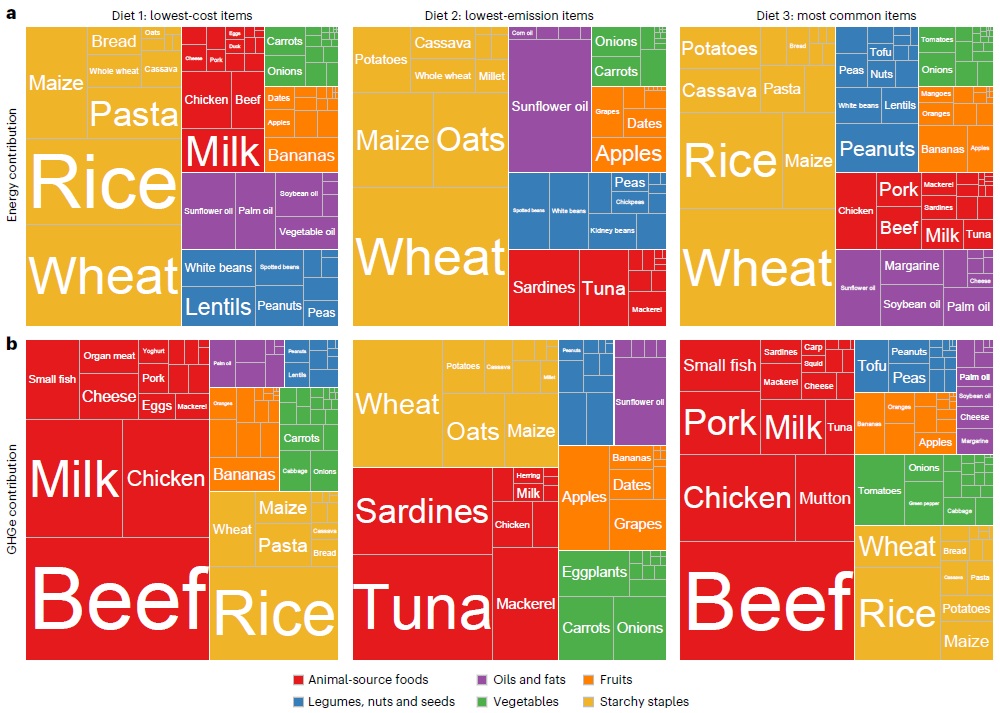

Energy (top) and emissions (bottom) contributions from different food groups within the three diets modelled by the study. Each column represents a different diet (left to right): lowest-cost, lowest-emission and most common items. The boxes are coloured by food group: animal-sourced foods (red), legumes, nuts and seeds (blue), oils and fats (purple), vegetables (green), fruits (orange) and starchy staples (yellow). Source: Bai et al. (2025).

Energy (top) and emissions (bottom) contributions from different food groups within the three diets modelled by the study. Each column represents a different diet (left to right): lowest-cost, lowest-emission and most common items. The boxes are coloured by food group: animal-sourced foods (red), legumes, nuts and seeds (blue), oils and fats (purple), vegetables (green), fruits (orange) and starchy staples (yellow). Source: Bai et al. (2025).